As its name implies, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) holds the conservation of wildlife and wild places as its central mission. Not surprisingly, many of the posts here on “Wild Things”—the blog for the WCS Archives—highlight WCS’s historical conservation efforts. This post, however, features a different kind of ‘conservation’: recent work performed on some of the Archives’ own materials.

As its name implies, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) holds the conservation of wildlife and wild places as its central mission. Not surprisingly, many of the posts here on “Wild Things”—the blog for the WCS Archives—highlight WCS’s historical conservation efforts. This post, however, features a different kind of ‘conservation’: recent work performed on some of the Archives’ own materials.

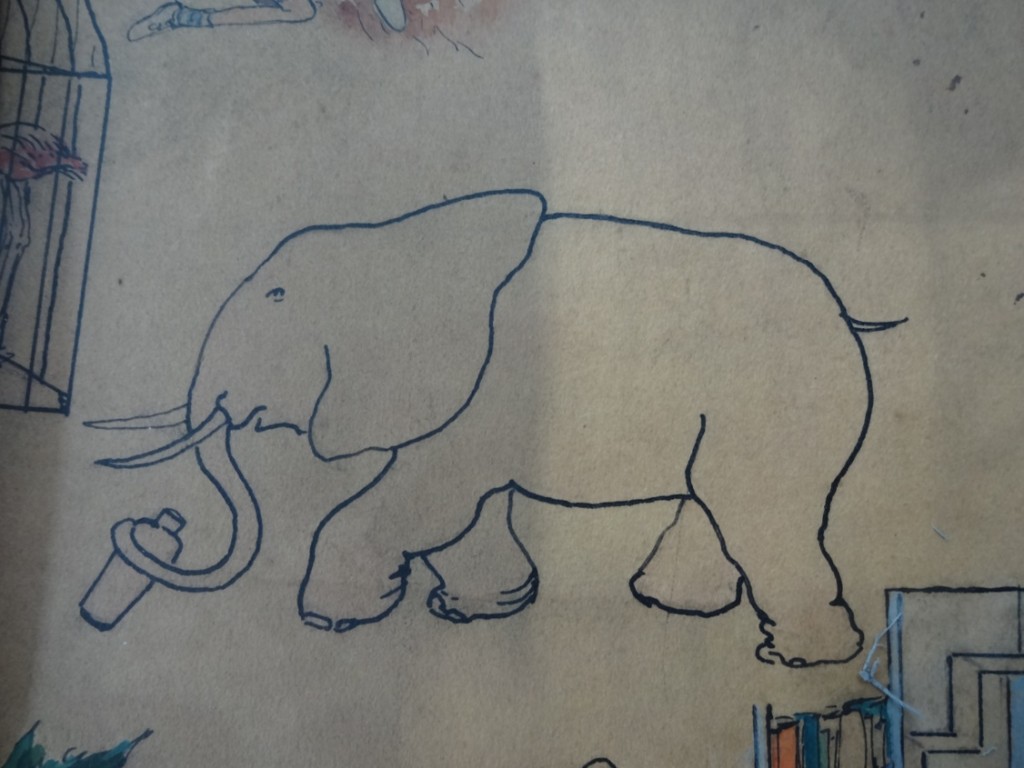

Detail from Helen Tee-Van’s illustration “Nonsuch, Alias…”, during treatment by conservator Paula Schrynemakers

Thanks to a 2014 Conservation Treatment Grant from the Greater Hudson Heritage Network, the WCS Archives was able to obtain much-needed conservation treatments for 10 historically important illustrations in its collections. The drawings—eight drawings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries of planned Bronx Zoo animal facilities and two painted maps from the 1930s depicting the facilities and work of William Beebe’s Department of Tropical Research in Bermuda—hold important aesthetic and historical significance.

Pre-conservation treatment photo of William T. Hornaday’s illustration of the yet-to-be-built Lion House at the Bronx Zoo

Post-conservation treatment photo of William T. Hornaday’s illustration of the yet-to-be-built Lion House at the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo drawings, some of which are by the Zoo’s first director, William T. Hornaday, depict some of the earliest structures at the Zoo, many of which were eventually landmarked. While the buildings that eventually became Astor Court did not exactly match these drawings in their details, the pre-construction illustrations of icons such as the Lion House and the Monkey House are still generally recognizable today.

Pre-conservation treatment photo of a design illustration of the yet-to-be-built Monkey House at the Bronx Zoo

Post-conservation treatment photo of the illustration of the yet-to-be-built Monkey House at the Bronx Zoo

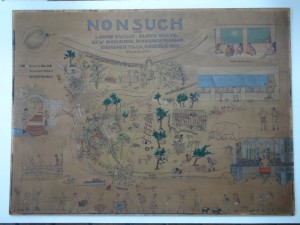

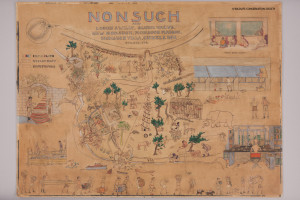

The two Department of Tropical Research (DTR) maps, created by illustrator Helen Tee-Van, celebrate the activities and people—and possibly animals!—of DTR’s research station on Nonsuch Island in Bermuda, which served as the home base for Beebe’s famous Bathysphere deep-sea dives.

Pre-conservation treatment photo of Helen Tee-Van’s illustration “Nonsuch, Alias…”, depicting the facilities and inhabitants of William Beebe’s Department of Tropical Research station on Nonsuch Island, Bermuda

Post-conservation treatment photo of Helen Tee Van’s illustration “Nonsuch, Alias…”, depicting the facilities and inhabitants of William Beebe’s Department of Tropical Research station on Nonsuch Island, Bermuda

The conservation treatments were performed by conservator Paula Schrynemakers, who carefully examined, cleaned, repaired, and stabilized each of the drawings. The cleaning was complicated by the fact that all of the inks and pigments used in the drawings were ‘fugitive’, and would have run with the application of any liquid cleanser or solvent. Nevertheless, the staff of the WCS Library and Archives have been delighted and amazed at the results Schrynemakers achieved; the illustrations now reveal colors and details that had been completely obscured by accumulated grime.

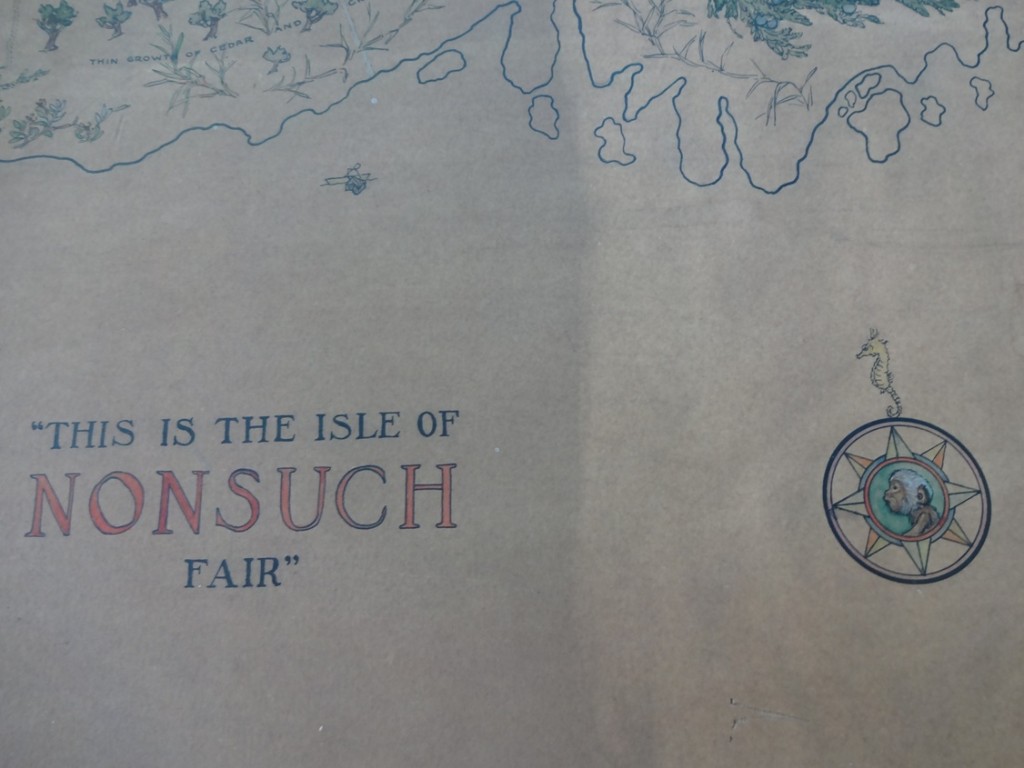

Detail of Helen Tee-Van’s illustration “This is the Island of Nonsuch Fair”, during treatment by conservator Paula Schrynemakers

Furthermore, Schrynemakers’ stabilization and repair work have strengthened and protected the drawings, which had become critically brittle and fragile over the decades since their creation.

Note: All pre- and mid-conservation treatment photos in this post were taken by the conservator, Paula Schrynemakers, while all post-treatment photos were taken by Matt Shanley, a photographer and colleague of Paula’s at the American Museum of Natural History. The original illustrations are part of the collections of the Wildlife Conservation Society Archives.

These are great! How were they cleaned, if not with any liquid?

Hi Cathy, These were cleaned by a conservator with a plastic eraser using specialized conservation methods. Thanks for your question!

Beautiful

You are quite fortunate to have in your employ a conservator who possesses not only great skills and conforms to the primary rule of conservation to maintain the integrity of the original form. The artist’s work was given new life. Kudos

Thanks Thomas, we were indeed lucky to find Paula and hire her for the GHHN grant! We’re delighted that she was able to preserve the evidence of these drawings’ long history as well as bring them closer to their original appearance.