William Bridges, in his history of the early years of the New York Zoological Society, relates that “in 1901, William T. Hornaday, the Bronx Zoo’s founding director, sought to acquire a ‘particolored bear’ for exhibition” (Gathering of Animals, p.222). In 1938 Hornaday’s successor, W. Reid Blair, acquired the Society’s first giant panda, Pandora. Pandora–and to a lesser extent her compatriot, Pan–was a smashing success. Her sojourn at the Society’s pavilion at the 1939-1940 World’s Fair was so popular that her return to the Bronx was celebrated with an enlarged enclosure and increased visitor viewing areas.

William Bridges, in his history of the early years of the New York Zoological Society, relates that “in 1901, William T. Hornaday, the Bronx Zoo’s founding director, sought to acquire a ‘particolored bear’ for exhibition” (Gathering of Animals, p.222). In 1938 Hornaday’s successor, W. Reid Blair, acquired the Society’s first giant panda, Pandora. Pandora–and to a lesser extent her compatriot, Pan–was a smashing success. Her sojourn at the Society’s pavilion at the 1939-1940 World’s Fair was so popular that her return to the Bronx was celebrated with an enlarged enclosure and increased visitor viewing areas.

Pandora and keeper at the Bronx Zoo, circa 1938-1941. Modern reproduction, from 1987 Giant Panda Exhibit press kit. Wildlife Conservation Society Publications and Printed Ephemera collection. Collection 2016.

Unfortunately Pan had never thrived at the Zoo, and Pandora passed away in May 1941, a month shy of what would have been her three-year anniversary. The Society quickly sought a replacement. Madame Chiang Kai-shek came to the rescue with the gift of first one, and then a second, young bear as thanks for U.S. aid to China during the Second Sino-Japanese War. That fall NYZS Executive Secretary John Tee-Van travelled to Sichuan to retrieve the pair; the Society’s 1941 Annual Report called their arrival “the most important acquisition of the year.” (p.8) The two pandas–soon named Pan-dee and Pan-dah–were presumed to be a breeding pair, but were later found to be both female.

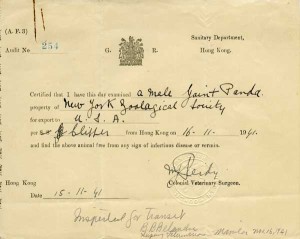

Veterinary inspection certificate for the supposed male of the pair, November 1941. New York Zoological Park. Office of General Curator. Lee S. Crandall records. Collection 1019.

Pan-dee and Pan-dah took up residence in Pandora’s panda moat and delighted zoo-goers for several years. On Halloween of 1951, however, the last of the pair died. That year’s Annual Report predicted the coming dearth in U.S. pandas by noting that prospects for a replacement were dim until and unless “conditions in the East […] improved to a far greater extent than [was] indicated for the immediate future.” (p.14)

Indeed, it wasn’t until the ‘Ping-Pong diplomacy’ of 1971 that the United States had any serious prospect of obtaining new giant pandas from China. At that time, New York City started lobbying for its zoo to be included among the beneficiaries of the newly thawed relations between the two countries. NYZS General Director William Conway received a number of inquiries regarding the Society’s plans–if any–to acquire the animals. One of the more fanciful came from publicist Burt Lucido, who offered to organize collecting expeditions to China; these would be funded by the zoo’s purchase of the captured pandas at a price of $50,000 each.

Conway’s reply to Lucido (pdf)

As Conway notes, the Society had already begun looking into the possibility of sending its renowned conservationist George Schaller to China to study pandas. In 1979 these efforts came to fruition, and China and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) signed an agreement to allow Schaller and others into the country to work on field research and captive propagation of the dwindling species.

Schaller memo on the WWF project (pdf)

Although Schaller and his colleagues worked throughout the panda’s range, the bulk of conservation work was conducted at Wuyipeng Research Station in the Wolong Nature Reserve. The efforts included radio tracking, the creation of guidelines for captive management, anti-poaching measures, redesigns of captive breeding facilities, and responses to the bamboo die-off of 1983-1984.

Schaller’s ‘Letter From Wuyipeng No. 2’ (pdf)

Meanwhile, Mayor Ed Koch was spearheading efforts to acquire pandas for the Bronx Zoo. In the 1980s, however, China ended the practice of giving the bears as outright gifts and shifted towards a policy of only exporting pandas as short-term loans. This was little deterrent to the mayor, however, and Conway’s correspondence from the era documents the lobbying of Koch and various other New Yorkers on the Society’s behalf. Eventually a special exhibit was arranged under the auspices of the Sister Cities program. The 1987 summer blockbuster, which attracted over a million visitors, featured youngsters Ling Ling (who would later be granted to the Ueno Zoo) and Yong Yong.

Press release announcing ‘Panda Mania’ (pdf)

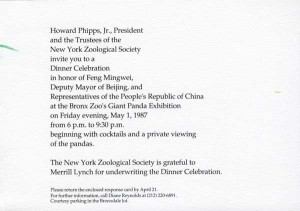

Cover and inside of the invitation to the exhibit’s opening dinner celebration honoring Chinese officials, April 1987. Wildlife Conservation Society Publications and Printed Ephemera collection. Collection 2016.

Cover and inside of the invitation to the exhibit’s opening dinner celebration honoring Chinese officials, April 1987. Wildlife Conservation Society Publications and Printed Ephemera collection. Collection 2016.

Since the 1980s, the New York Zoological Society–now the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS)–has continued to focus on international consortia working to protect pandas. Between the 1980s and the early 2000s WCS participated in WWF and IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) panda conservation, management, and species survival programs, and Conway himself was a member of the American Zoological Association’s Giant Panda Task Force and Giant Panda Conservation Action Plan. In all that time, however, WCS has not sought another panda of its own. As a New York Times article from an era of renewed panda-longing noted, George Schaller was against the loan program, and the Society felt that several factors contraindicated the acquisition of new pandas. The crux of these reasons still hold today: WCS prefers educational exhibits of animals tied to its conservation programs over isolated blockbusters. So, until and unless another wave of ‘Panda-Mania’ strikes, the documents, images, and ephemera in the collections of the WCS Archives remain the best–and only–way to view a giant panda in the Bronx. In fact, the Archives holds so much material showcasing the Society’s pandas, and especially Pan-dee and Pan-dah, they are bound to be the topic of another Wild Things blog post someday!

This Zoo Keeper is our Grand Father William “Bill” Dalton.

We would love to see anything else you have on him.

Thank You

The Daltons

Thank you cousins for sharing.

Would also love to see anything else you have on my Grandfather William Dalton.

Great article.

Joanne