This post was written by Kimio Honda, Studio Manager in WCS’s Exhibition and Graphic Arts Department. This is the second part of a three-part series on the Bronx Zoo’s Rainey Gates; for part 1, on Paul J. Rainey, see here.

This post was written by Kimio Honda, Studio Manager in WCS’s Exhibition and Graphic Arts Department. This is the second part of a three-part series on the Bronx Zoo’s Rainey Gates; for part 1, on Paul J. Rainey, see here.

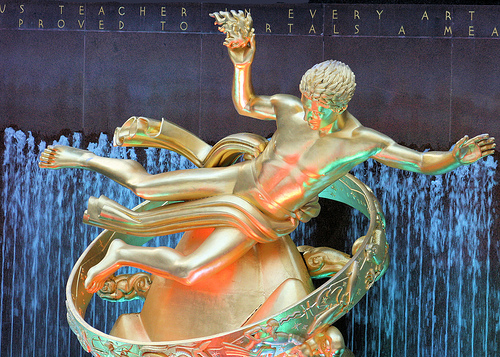

Paul Manship, creator of the Rainey Gates, is a well-known American sculptor. Even if you haven’t heard his name, you may know one of his most prominent works: the bright gold Prometheus at the Rockefeller Center. His works are at the Metropolitan Museum and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. Manship served as chairman of the board at what is known today as the the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which also holds dozens of Manship works.

Mrs. Grace Rainey Rogers, Paul J. Rainey’s sister, may have started a conversation with Paul Manship in Paris in 1924 about the commission to create the gates, while she was posing for her portrait figurine, according to Paul’s son John in his 1989 book, Paul Manship. Mrs. Rogers was a great patron of arts, and some New Yorkers may recognize her name from the Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She served on the boards of the Metropolitan Museum, MoMA, and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

According to John Manship’s book about his father, the Rainey Memorial Gateway was a “dream commission” in terms of the scope, creative freedom, money, and time, and it was certainly one of his most important commissions. He returned from Paris to New York in 1925 and, in return for his promise to create the gates, Manship secured a loan of $30,000 from Mrs. Rogers which he used to finance the purchase of five brownstone tenements on East 72nd and 73rd Streets. He didn’t acquire these properties for himself and his wife alone, but to provide housing and studios for his friends, colleagues, and relatives.

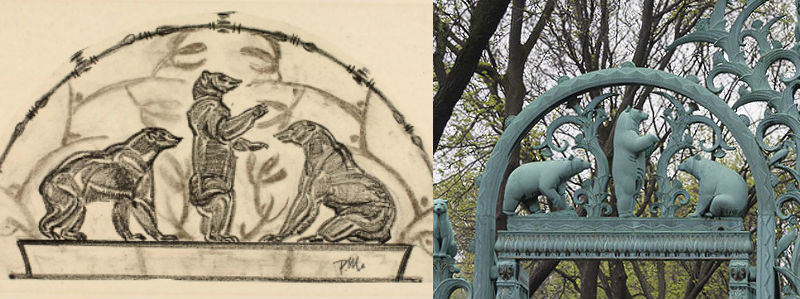

Detail of Rainey Gates. (L) Image from Smithsonian American Art Museum. (R) Image from photo by Kimio Honda.

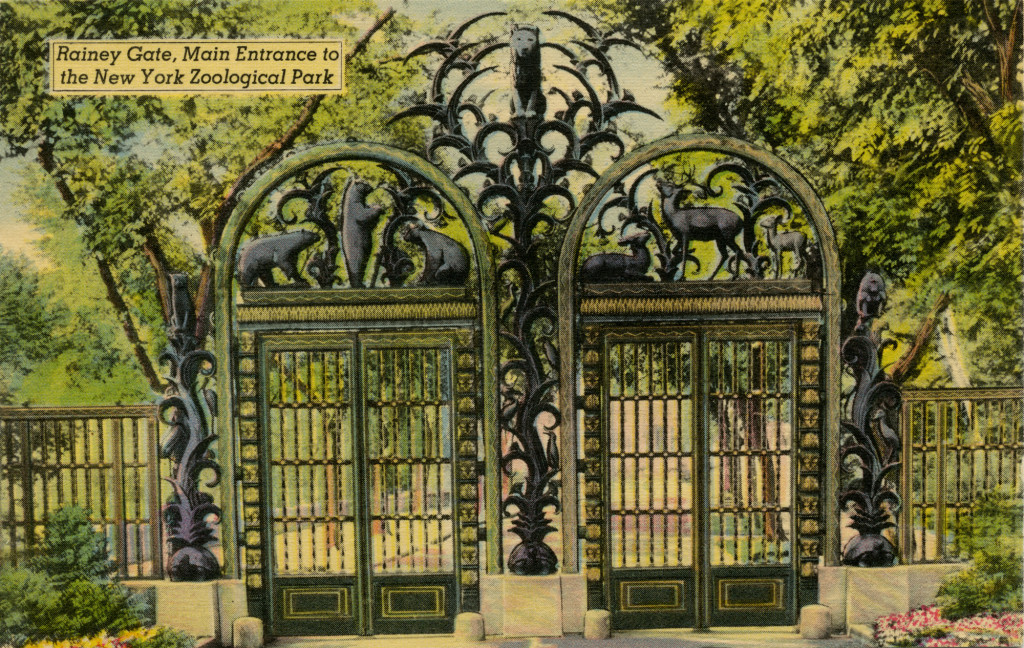

Manship’s original idea for the Rainey Gates was a wrought iron fencing with bronze sculptures. He resolved to study the great works of wrought iron in Spain and set off the following year for a driving trip through Spain with a few of his friends. In the end, unable to come up with a satisfactory design based on the delicate wrought iron to match the desired scale, he chose to create the gates entirely in bronze.

As Carol Hynning Smith describes in Drawings by Paul Manship (1987), Manship worked on scale models and the creation of full-sized details for nearly five years with the aid of some fifteen assistants. Two more years were needed for bronze casting and assembly. The bronze work was done in Belgium by the company Manship had inspected and set his eye on previously. The press release for the dedication, written by WCS Curator of Publications William Bridges and held by the WCS Archives, states that the bronze alone weighed about 28 tons.

A sister’s commission for a monumental work of art in memory of her big-game-hunter brother, a conversation in a Parisian art studio, five houses in Manhattan for family and friends, a research trip with friends by car through Spain, casting and assembling bronze pieces in Belgium and shipping 28 tons of them to New York… to think that this was all about one piece of art, however grand and beautiful as it may be and however renowned the artist may have been, I cannot help but feel that the whole story has the character of a fairy tale, in comparison to the hurried world we live in today. This feeling gets even stronger when you think of the fact that this project carried on right through the Great Depression.

Stay tuned for next week’s post, which takes a look at the individual animals featured on the gates.

Thank you for keeping the history alive.