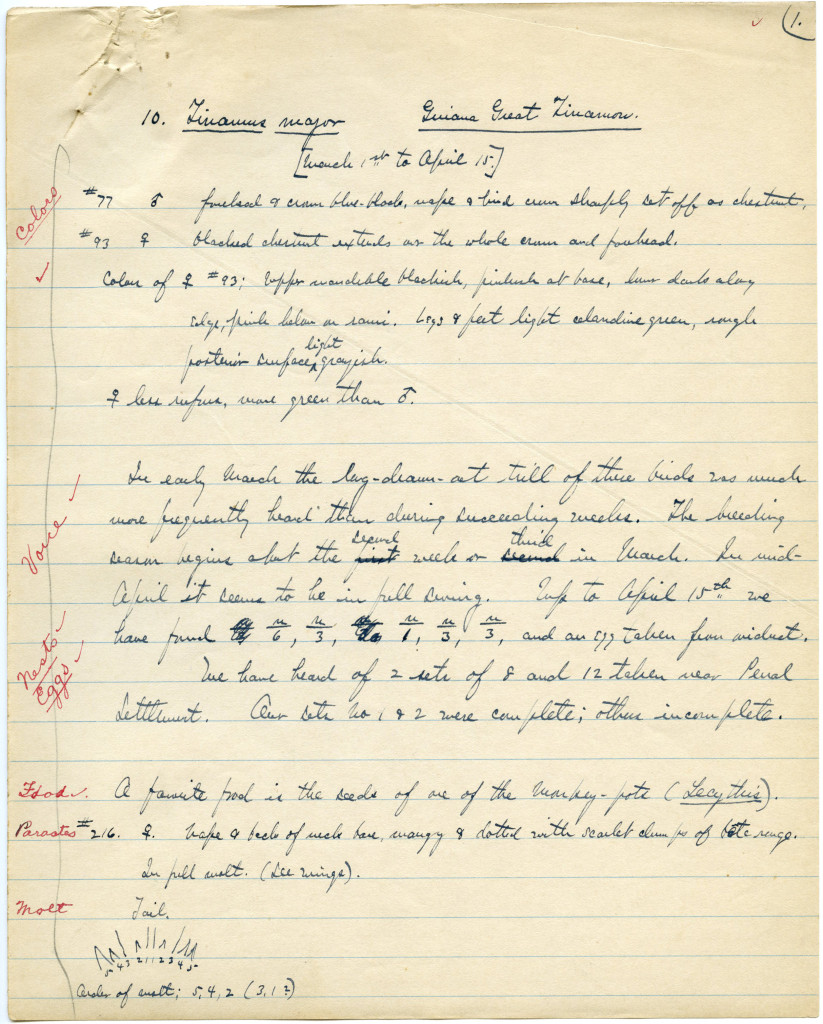

Why? According to William Beebe, why was “the question which makes all science worthwhile.” Why, for instance, do tinamous of the genus Tinamus have rough skin on their lower legs while tinamous of the genus Crypturus have smooth skin? Why do hoatzin populations seem to gather in nodes rather than being found throughout tropical forests?

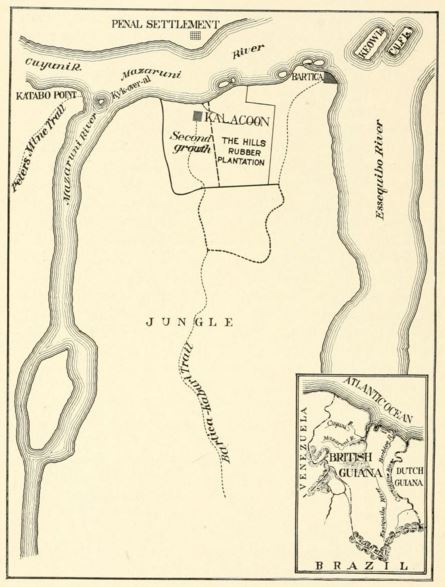

For Beebe, who began his career as the Bronx Zoo’s first Curator of Birds, the answers to these and other questions about wildlife could only come through intensive, in situ observation. With the professionalization of science in the late nineteenth century came not only the development of specializations but also a turn indoors, in the field of biology, to the study of collected specimens. Beebe and likeminded naturalists, however, believed that nature could best be understood in nature. And so it was to facilitate this ecological approach that 100 years ago this month, the New York Zoological Society founded its first Tropical Research Station. Under the direction of Beebe, the Station was established in a small house, called Kalacoon, on the Hills Rubber Estate, near Bartica, Guyana.

Map of the Tropical Research Station’s general field of work. From Tropical Wild Life in British Guiana (1917).

It’s nearly impossible to write a short-ish blog post on this event. For one, I find it difficult not to get lost in the details–let alone the meanings–of the 1916 expedition, which lasted six months and in which Beebe and his colleagues studied not only native birds like the tinamou and the hoatzin but also the area’s reptiles, amphibians, and mammals. With the help of local assistants, Beebe and his team mapped out a zone of jungle around Kalacoon equal in size, as Beebe noted in the Society’s 1916 Annual Report, to that of Central Park, and they confined their intensive explorations to this area. Although they would bring back over 300 animals for the Bronx Zoo, collecting, Beebe insisted, “was wholly subordinate to the scientific investigation which was the main object of the Station.”

First page of Beebe’s notes on his six-weeks’ observation of Tinamus major, likely 1916. WCS Archives Collection 1005B

Beebe and his staff would record their work in popular and scholarly journals as well as in the popular part-travelogue, part-nature study Tropical Wild Life in British Guiana (1917). (Even if you never read the book, I hope you’ll find a chance to read this passage about a hoatzin chick Beebe decides against collecting, which showcases the masterful storytelling that would make him a hit with popular audiences.) There was so much to say that in 1918, Beebe would publish another book about his work at the Tropical Research Station in Kalacoon. Jungle Peace, as it was known, was so popular that it required five reprintings in its first five months, according to Kelly Enright’s Maximum of Wilderness (2012), which features a chapter on how Beebe influenced American perceptions of tropical forests.

Theodore Roosevelt and his wife Edith were the first visitors to Kalacoon, and Beebe and his staff, who had just arrived themselves, fretted about getting the station ready for the visit of such auspicious guests. Beebe is seated at the far end of the table, Mrs Roosevelt is seated nearest the camera, and President Roosevelt is next to her. WCS Photo Collection

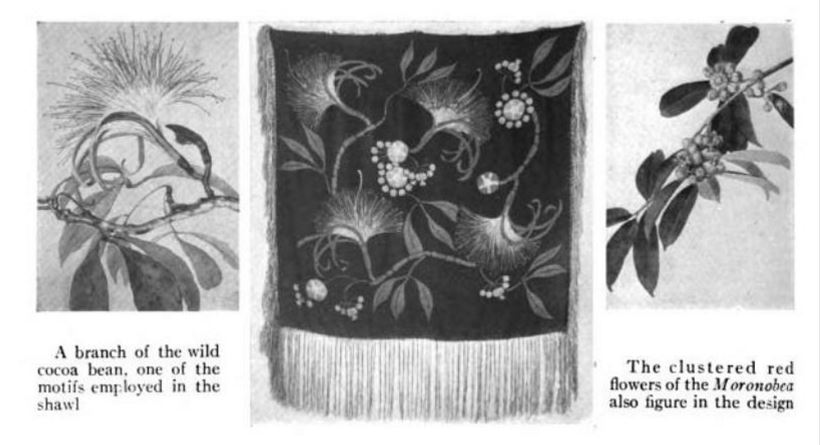

Apart from distilling down the expedition’s details, there’s also the challenge, in writing about this first Tropical Research Station, of staying on track–a challenge I face every time I start looking into the Department of Tropical Research (DTR), as Beebe and his staff would be known by 1918. It’s a testament to the fascinating characters associated with the DTR, which existed until 1965, that a single step away from them leads to everything from King Kong to Crosby, Stills, and Nash. (More on those connections in another blog post!) In 1916, Beebe was accompanied at Kalacoon by researchers G. Innes Hartley and Paul G. Howes, Bronx Zoo keeper and collector T. Donald Carter, and artists Anna Taylor and Rachel Hartley. Throughout its history, the DTR included artists among its staff members. They worked alongside the scientists to document the animals and plants they observed–capturing the color and detail that photography could not at the time–and the WCS Archives holds over 1,200 of these expedition illustrations. Compared with some of the DTR’s later artists, I know relatively little about these early ones, but just a tiny bit of digging revealed that Anna Taylor is Anna Heyward Taylor, a South Carolina artist who would go on after her work with the DTR to become associated with the Charleston Renaissance. Taylor worked with Beebe in Guyana in 1916 and again in 1920. Following the 1920 expedition, Taylor transformed some of her botanical drawings into prints and batik textiles. These were shown at the American Museum of Natural History and the Brooklyn Botanical Garden, and according to Taylor’s Wikipedia page, they may represent the “first time microscopic details of plants were used in decorative art.”

Taylor textile shown at the American Museum of Natural History. From the Museum’s journal, Natural History, 1922

And finally, in writing about this expedition, it’s hard not to go on at length about the influence this early work had. Beebe and his staff were the first to answer some of those “why” questions about the life histories of animals that Beebe found so important, but they were also the first to ask those questions–and the first to seek their answers outdoors. Theodore Roosevelt, whom Beebe considered a friend, correctly intuited in the introduction to Tropical Wild Life in British Guiana that the founding of the Tropical Research Station “marks the beginning of a wholly new type of biological work, capable of literally illimitable expansion.” The DTR itself would expand upon this work, later taking their pioneering practice of intensive field observation to the Galapagos Islands, Bermuda, and other marine environments before returning to the tropical forests of South America in the 1940s. And they would thus help to lay the foundation for field biology, both inside WCS–from the Institute for Research in Animal Behavior, which subsumed the DTR in 1965, through today’s Global Conservation Program–and beyond.