The vast majority of the documents in the WCS Archives are written by people speaking as themselves. They may be speaking as representatives for a larger collective, such as the Society, or a professional organization, or even–in the cases of some Congressional testimony transcripts–as representatives for the zoo profession as a whole. Every now and then, however, we come across examples of people speaking not in their own voices, but in those of animals.

The vast majority of the documents in the WCS Archives are written by people speaking as themselves. They may be speaking as representatives for a larger collective, such as the Society, or a professional organization, or even–in the cases of some Congressional testimony transcripts–as representatives for the zoo profession as a whole. Every now and then, however, we come across examples of people speaking not in their own voices, but in those of animals.

Sometimes these documents purport to have been written by specific animals–indeed, sometimes by actual Bronx Zoo animals–other times they are written from the point of view of fictional animals. All, however, use a combination of humor, anthropomorphism, and empathy to get their point across.

The earliest example I personally have identified in the collections, this “Announcement of Convention” from the (fictional) International Association of Captive Gorillas, seems to have been an actual, albeit tongue-in-cheek, convention announcement. [Link goes to the pdf, scanned from WCS Archives Collection 1019.] In September 1941 Jean Delacour–who worked closely with the Bronx Zoo’s curators in his capacity as the New York Zoological Society’s Technical Advisor–attended a convention of (institutions holding) captive gorillas in San Diego; the rest of the folder includes notes from the meeting, follow-up correspondence, and so on. This convention announcement traded on in-jokes and topical allusions: everyone who received it would know who (else) was being invited based on their knowledge of the purported gorilla attendees, right down to the fact that the invited French gorillas represented the Free French government, and therefore the human invitee could be presumed to not be one of the Vichy collaborators.

More importantly, the announcement let the invitees–and today’s readers–know what actual work was on the table: “Business to be conducted is said to be along the lines of better understanding of gorilla problems, furthering of conservation of gorillas, both wild and captive, and publication of more accurate information concerning the life, character, and general future status of gorillas”. From all indications, while the gorillas named in the announcement didn’t gather to speak of any of these things, their human representatives–including Delacour, San Diego Zoo Director Belle Benchley, and the Ringling Brothers Circus–did.

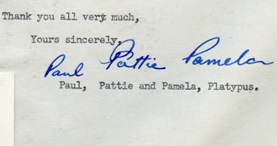

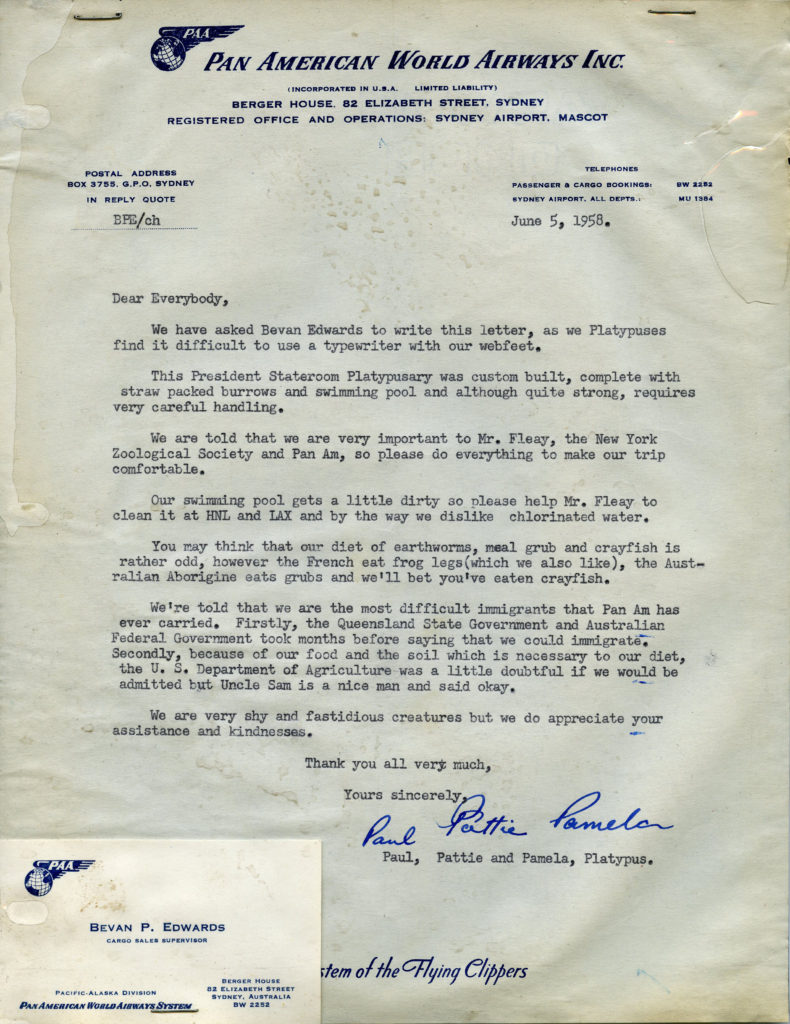

Similarly, the following missive, from the webbed feet of three soon-to-be residents of the Bronx Zoo, is also at its heart exactly what it purports to be: a letter describing the care and feeding that Paul, Pattie, and Pamela would need while in transit between Queensland, Australia and New York City (a journey which, in 1958, required numerous layovers).

Platypus air transport care and handling instructions, as ‘written’ by Paul, Pattie, and Pamela, and ghostwritten by Bevan Edwards, June 5th, 1958. WCS Archives Collection 2047.

I presume that the gimmick of writing as the platypus trio was intended to get the crew staffing each flight segment to appreciate their cargo a bit more readily than if the same instructions had simply been handed over by Mr. Edwards as his own dictates.

I believe that New York Zoological Society [NYZS] General Director William Conway also banked on that anthropomorphic humor -> appreciation/empathy -> care equation when he wrote satirical addresses in the voices of a Canada Goose and a lab chimpanzee. In the first of these, a speech at the March, 1964 Midwinter Meeting of the American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums that was later (in 1968) published in the magazine Modern Game Breeding as “Branta canadensis to the International League of All Wildfowl,” Conway takes on the persona of the “481st Hereditary President, 11th Dynasty” of the International League of All Wildfowl. [Link goes to the pdf of the 1964 version, scanned from WCS Archives Collection 1028.] Despite mentioning everything from the dangers of nuclear experimentation (top of page 2), to the racial violence of the segregation era (middle of page 2–this connection is made more strongly in the 1968 version) to Marlin Perkins’ television hit Wild Kingdom (bottom of page 5, Perkins was Director of the St. Louis Zoo at the time), Conway’s overall message of concern for wild waterfowl–and of the need for greater concern–remained clear. Throughout he lamented the effects of hunting and habitat destruction on non-captive populations, and chided zoos, private aviculturists, federal fish and wildlife officials, and others involved with captive waterfowl for their inaccurate identification practices, tendency to value the number of species in a collection over keeping sustainable breeding groups, and expecting what breeding groups they did keep to manage in spite of a dearth of knowledge about the particular mating habits of the species being bred.

As Conway had the 481st Hereditary President say, (pages 7-8): “A zoo could be an important outpost of the wild world in man’s world; it could promote interspecies understanding and appreciation, but it does not. How can we hope to represent our species in a forum which often fails even to identify us, which, at most, devotes five lines of text to our cause on signs so unimaginative that visitors rarely pause to read them? […] Our species everywhere are diminishing. The time is not far off when many of us will join the Heath hen and the Laborador [sic] Duck but look not to the game breeder or the zoo for salvation through captive breeding. How many of our captive populations have died out through their indifference? How many have been lost in the collections of game breeders who have lost interest in their hobby or died without providing for its continuance? How much has been lost through the stamp collecting propensities of zoos and game breeders alike who have failed to maintain sufficient breeding stock of important species?”

These were very real questions, despite the fictional mouthpiece, but It should be noted that Conway–a zoo director–was asking them in front of a room full of fellow zoo directors, curators, and other colleagues. A somewhat different dynamic was at play in his lab chimpanzee speech. This speech was originally given at a meeting of the New Rochelle Medical Society in February, 1977, and was revised and published the following year in NYZS’s Animal Kingdom magazine as “Memo from a Laboratory Primate.” In comparison to the goose speech the chimp piece is no less humorous (or satirical, rather), but it is considerably more graphic in its examples and strident in its tone.

(Thumbnails: Links to selected pages from the typescript of the revised version of Conway’s “Memo from a Laboratory Primate,” published in the August/September 1978 issue of the New York Zoological Society’s Animal Kingdom magazine. )

The anti-vivisectionist slant–condemning the use of chimpanzees and other primates for medical research of dubious scientific value, especially when it led to the deaths of the animals involved–is perhaps understandable given the background of primates becoming more and more difficult to collect from the wild due to habitat loss, increasing export restrictions, and political instability in the animals’ home ranges in the wake of decolonization. However I suspect that the fact that Conway was a zoo director, and not from an institution involved in medical research, also had something to do with it.

I don’t have any such speculation for a deeper context to this final bit of monkey business, a congratulations letter written in response to the publication of the chimpanzee piece above: