In 1922, the Bronx Zoo displayed the first duck-billed platypus to be shown live in a zoo outside of Australia. That was the last platypus to be seen in the United States for the next quarter century, until the Bronx Zoo again exhibited platypuses in April 1947. The Bronx Zoo’s parent organization, the New York Zoological Society, had begun working with the famed Australian naturalist David Fleay to acquire platypuses in the winter of 1945-1946. The original hope was to display the platypuses that summer, but several factors thwarted this plan. Capture and shipping difficulties, a threatened maritime strike, and a housing shortage that led the US government to ban all non-housing construction ultimately led the Society to call off the acquisition until the following year.

In 1922, the Bronx Zoo displayed the first duck-billed platypus to be shown live in a zoo outside of Australia. That was the last platypus to be seen in the United States for the next quarter century, until the Bronx Zoo again exhibited platypuses in April 1947. The Bronx Zoo’s parent organization, the New York Zoological Society, had begun working with the famed Australian naturalist David Fleay to acquire platypuses in the winter of 1945-1946. The original hope was to display the platypuses that summer, but several factors thwarted this plan. Capture and shipping difficulties, a threatened maritime strike, and a housing shortage that led the US government to ban all non-housing construction ultimately led the Society to call off the acquisition until the following year.

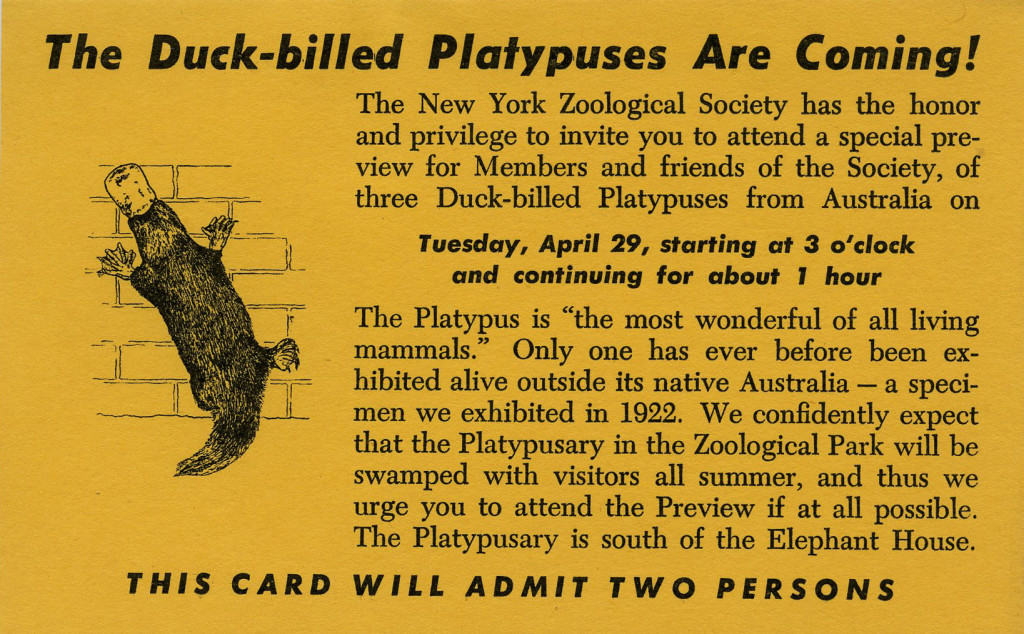

- Invitation to the opening of the platypusary, April 1947. Wildlife Conservation Society Publications and Printed Ephemera collection. Collection 2016.

On April 25, 1947, the platypuses—named Penelope, Cecil, and Betty Hutton—made their debut to much fanfare. The opening press release (pdf), as well as the New York Zoological Society annual report for 1947 relate how several of the Society’s departments pulled together to care for the delicate animals. The Aquarium and the Farm-in-the-Zoo provided eggs, earthworms, frogs, and other creatures for the platypuses’ food, the Education department set up a public address system around the exhibit and ran the Question House, which answered so many inquiries regarding the unfamiliar animals that these were broken out into a separate reporting category, and the Construction and Maintenance department was finally able to build a platypusary to house the trio.

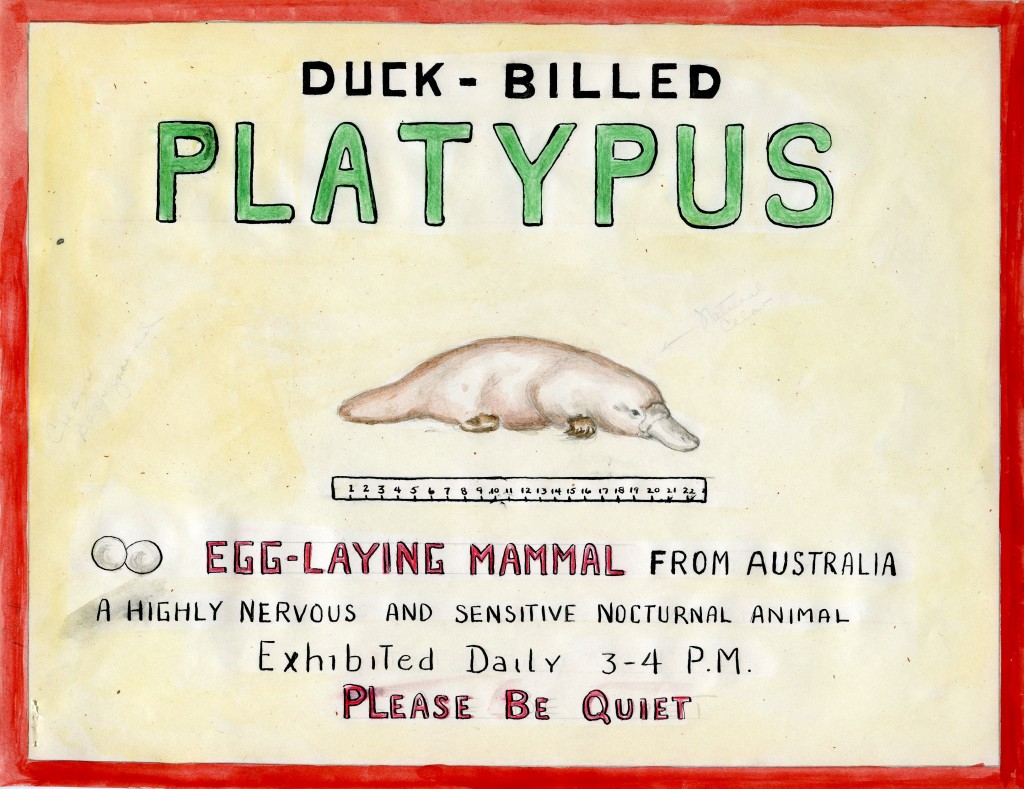

The platypusary, a special enclosure designed to mimic conditions in the platypuses’ native riverbed habitat, had been designed by Fleay and built to his strict specifications to minimize the disturbances that keepers and the public would impose upon the sensitive animals.

Mockup of exhibit graphic warning the public of the fragility of the platypus, April 1947. James G. Doherty records, 1937-2005. Collection 1047.

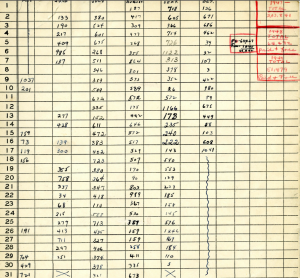

The platypusary was hugely successful during its twelve-year run. Although the exhibit only showed one platypus at a time, and was only open for one hour per day, the average daily attendance in 1947 was 1,222. The exhibit was so overwhelmed that for the 1948 season a five-cent fee was imposed in hopes of controlling the crowds. Even so, paid attendance records show that hundreds of visitors came to view the platypuses during their daily hour, and there were seven days over the next decade where the daily total again exceeded 1,000 visitors.

Unfortunately the platypuses’ delicate temperaments prevented the Zoo from achieving its highest hopes for the trio—that they would be the founders of the first and only permanent platypus population outside of Australia. Betty Hutton succumbed to a heat wave in September of 1948, and although Cecil and Penelope provided plenty of fodder for the Society’s dreams (including a false pregnancy that caused the platypuses to be taken off exhibit for part of the summer of 1953), nothing came of their courtship attempts.

During one of these courtship episodes, in July of 1957, Penelope went missing. The New York newspapers, which had been avidly following the platypuses’ affairs, quickly proclaimed that Penelope had had enough of Cecil’s amorousness, and had wanted some rest. The story of nightly searchers of the Bronx Zoo by a team of curators and keepers spread across the nation, reaching Time Magazine [subscription required to view full article], and letters of sympathy and encouragement poured into the Society. It should be noted that some of this correspondence was more tongue-in-cheek than sympathetic: the Zoo received one telegram from Miami reporting that Penelope had been spotted in Cuba, in the midst of the Cuban Revolution.

Penelope was never found, and two months later Cecil passed away. The following spring the Society and Fleay worked together to bring three more platypuses to New York, taking advantage of the intervening decade’s improvements in air travel to send the new trio, Paul, Pamela, and Patty, via air freight. Once again, the capture, transport, and arrival of the platypuses was much-heralded by the Society.

The New York Zoological Society News: Australian Platypus Expedition (pdf)

Sadly, Paul, Patty, and Pamela did not fare well in their new home. They finished the 1958 exhibition season, but by the following spring all three had perished. The United States has not had a platypus since. Although common in their native habitat, and listed as a species of least concern by the IUCN (which determines the international conservation status of wildlife), the Australian government strictly regulates export of the animals; zoo-goers wishing to see a platypus today must travel down under to do so.